The recent death of Pat Buckley, William F. Buckley's wife, reminded me of my own association with the father of modern American conservatism, which had ceased to have any meaning for me when Bill came out against the trade embargo on Cuba some 15 years ago. If conservatism is just another word for opportunism, as its critics contend, then Buckley, as usual, was ahead of the pack. But no matter; it was not on the issue of Cuba that our paths diverged in the 1980s, but on the question of what constitutes anti-Semitism.

One of the National Review's own staff writers, Joseph Sobran, had been accused of anti-Semitism because of his defense of John Demjanjuk, an autoworker from Cleveland, OH who was accused of being a notorious concentration camp guard known as "Ivan the Terrible." Sobran believed that this was a case of mistaken identity (as both the Israeli Supreme Court and the U.S. Sixth Court of Appeals would later find). Sobran pointed out that it was the height of hypocrisy to accept Kurt Walheim, an undisputed former Nazi (can one be a former Nazi?) as head of the United Nations and later president of Austria, while the U.S. aimed not its guns but its cannons at a Cleveland autoworker in an almost successful campaign to have him hanged for another man's crimes.

This seemed to me a most reasonable position, but Buckley saw it otherwise. First he came to Sobran's "defense" with this statement: "Sobran is not a naked anti-Semite, nor, in my opinion, a crypto or even a latent anti-Semite." Finally, however, Buckley fulfilled the promise of that initial statement and came out against his friend and protegé whom everyone supposed would some day be his successor at the National Review. Of course, Buckley was entitled to his opinion. What he was not entitled to do, in my opinion, was to fire Sobran because of his. Buckley compounded the offense by agreeing with neoconservatives that Sobran's statements could be interpreted as "anti-Semitism" of a kind, which Buckley defined as any criticism at all of Jews or Israel. Buckley wrote that this prohibition was a "welcome taboo" in order to avoid "another genocidal catastrophe." So poor Sobran, whose only "offense" was Zola's in championing the cause of an innocent man, was indirectly accused of abetting another "genocidal catastrophe."

I wrote an article in the old New York Tribune where I turned my own small polemical skills on Buckley: "The argument ad Holocaust is a wearysome cliché of the liberal-left and of neo-conservatives who have abandoned their old comrades on the left but have not been able to escape the pernicious imprint that four decades of intellectual anemia has left on their minds. The thrust of this argument is always the same — we haven't learned from Nazi Germany's past and are condemned to repeat it in America. Just when, no one knows, but it's always around the corner. It is just this kind of fashionable paranoia thar finds parallels between Auschwitz and Bitburg, Sobran and Rosenberg (the Nazi ideologue), the National Review and Volkischer Beobachter (the Nazi party organ)."

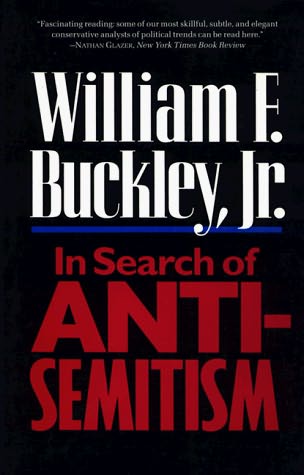

My article did not go unnoticed or unanswered. In fact, Buckley devoted an entire book to answering it entitled In Search of Anti-Semitism. My article is quoted there though not rebutted.

There is a sequel to this story. In 2005, 20 years after the Sobran affaire, the National Archives released a letter written in 1982 by William F. Buckley to Judge (later Supreme Court Justice) John Roberts, Jr. on behalf of a Russian-language lecturer at Yale, Vladimar Sokolov, who was accused of writing anti-Semitic newspaper articles in Nazi-occupied Russia during World War II, and was facing, like Demjanjuk, denaturalization and extradition. In effect, while Buckley was supporting an acknowledged Nazi propagandist from his alma mater, he accused and fired a colleague for doing publicly what he was doing privately. Sokolov eventually admitted the charges against him and fled to Canada ahead of a court order to extradite him to the Soviet Union. The U.S. Sixth Circuit Court eventually ruled that the Justice Department's Office of Special Investigation (OSI) had perpetrated "a fraud on the court" in claiming that Demjanjuk was Treblinka guard "Ivan the Terrible." It might be noted, en passant, that this same Office of Special Investigations is in charge of prosecuting another innocent man, Luís Posada Carriles.

I have just sent a note of condolence to Bill Buckley along with my best wishes for his continued good health. (In truth there is no worse fate that can befall a man than to outlive a wife of more than 50 years). No man fought Communism harder in what José Martí called the "paper trenches" than did WFB and his lapses in judgment should not obscure that fact, not even his longstanding opposition to the Cuban trade embargo.

No comments:

Post a Comment