Part I (1902-1940)

The Cuban Republic came into being after a War of Independence that resulted in the death of nearly a quarter of Cuba's population and the destruction of most of the island's infrastructure and economy. In addition to such internal problems, Cuba also had to deal with the intervention and occupation of the island by the U.S. after the conclusion of the Spanish-American War (1898), a minor but calamitous episode within the context of the greater Cuban War of Independence begun by José Martí (1895-1898).

The Cuban Republic succeeded despite the great obstacles placed in its way by U.S. imperialism at its birth. These obtacles Cubans never ceased to fight and eventually defeated long before Castro came on the stage to renew a conflict that had already been resolved largely in Cuba's favor.

Cuba's first democratically-elected president (1902-1906), Tomás Estrada Palma, defeated an American attempt to acquire not one but ten military bases on the island as well as the Isle of Pines (Cuban ownership of which was confirmed in the Hay-Quesada Treaty). He also insisted that the one base that was granted to the Americans be leased rather than ceded, which meant that Cuba still retained sovereignty over Guantánamo thereby setting the stage for its return some day to Cuban jurisdiction. In fact, Guantánamo Naval Base would have been returned decades ago if it had not been for Castro, as the Panama Canal was returned to Panamanian jurisdiction. President Estrada Palma was known as the "Honest President" because he broke with the tradition of graft and corruption introduced to Cuban political life by the Americans.

Estrada Palma was succeeded in the presidency, after an armed uprising quelled by the U.S. at his request and another brief U.S. occupation (1906-1909), by his democratically-elected rival José Gómez, whose administration (1909-1913) was characterized by both its corruption and the full recovery of Cuba's economy from the ravages of the recent war.

Gómez was succeeded in turn, also as a result of democratic elections, by Mario García Menocal, the first and only Cuban president to serve two consecutive terms (1913-1921). The major event of his administration was the First World War, which brought unprecedented prosperity to Cuba as the price of sugar climbed to astronomical levels never to be seen again. Although Menocal joined the Allied side in the War and even instituted a draft, he refused repeatedly U.S. requests to send Cuba's sons overseas to fight in Europe under the American flag. The war ended without a single Cuban casualty. Cuba also joined the League of Nations, which the U.S. did not. A Cuban, in fact, served as its president, which proved that the world as a whole accepted Cuba's sovereignty despite American intrusions on it.

Menocal was succeeded in democratic elections by Alfredo Zayas (1921-1925), a nationalist who also defied U.S. interests in Cuba. Zayas' administration was corrupt; but when the even more corrupt administration of Warren G. Harding sought to impose on him an "honest cabinet" of its own choosing, Zayas at first assented (to get the U.S. war ships threatening intervention to go home) and then immediately fired the U.S. puppets and appointed his own men. This was the first time that the U.S. had been openly defied in Cuba and the U.S. did nothing. This lesson would not be lost on the Cuban people.

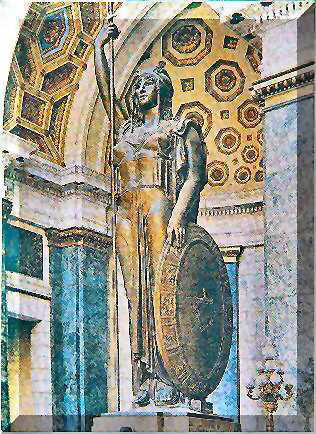

Zayas was succeeded, yet again in democratic elections, by Geraldo Machado (1925-1933), the most popular Cuban president as well as the most unpopular. His public works programme transformed Cuba into a modern nation. He built the Capitol as well as the Central Highway, which ran the whole length of the island, among hundreds of other civil works projects. He was so popular that at one time all the Cuban political parties supported him. Machado had made a pledge when he was elected not to seek re-election. He kept this pledge by convincing Congress to prolong his presidential term, which it did gladly. The Cuban people did not receive this violation of Cuban democracy as gladly, however. This "prolongation of powers" led to Cuba's first popular revolution, which succeeded in ousting the democrat turned dictator. Machado believed that this revolution was abetted by the U.S. and before resigning made anti-American declarations for the first time in Cuban political history. The Machado opposition was even more nationalistic and anti-American in its rhetoric.

The Revolution of 1933, with its succession of provisional presidents, juntas and even a counter-revolution, nevertheless succeeded in abrogating in 1934 the Platt Amendment, which had been imposed in 1902 and gave Americans the right to intervene at will in Cuba to protect "our" (read their) interests. With the scrapping of the Platt Amendment Cubans exercised for the first time full national sovereignty. There would be no more American interventions in Cuba. Martí's dream and the dream of all Cuban patriots was finally realized thanks to Cuban resolve and another Roosevelt's "Good Neighbor" policy, which was itself the product of American experiences in Cuba.

If there is a revolution that Cubans should celebrate it is the Revolution of 1933, which was everything that a future revolution was not — nationalistic, progressive and brief. The 1933 Revolution endowed the Cuban people with social rights that no other people on earth enjoyed or would enjoy for decades, including paid maternity leave and a 35-hour work week (for which the employee was entitled to 40 hours compensation). It avoided, moreover, the fashionable extremes of the age, shifting neither to the right and fascism, nor to the left and communism.

Although the Generation of 1933 hated Machado and his cohorts no less than the Generation of 1953 despised Batista and his, the death penalty was not imposed on any of the collaborators of the regime: capital punishment for political crimes was then unknown in Cuba and the firing squad had not been used on the island since colonial times.

The greatest virtue of the 1933 Revolution — the reason for its success, if you will — was its exemplary brevity. In just three years (1933-1936) it had run its course and normality was restored to the island. The final act of the 1933 Revolution was the Amnesty Law of 1936 which freed all Machado officials held in detention (very few) and restored to them their full civil rights. In the elections also held that year many of them were returned to office, one even became Speaker of the House of Representatives.

In the 1936 presidential elections Josê Mariano Gómez, son of Cuba's second president, was elected its sixth constitutional president. In a further test of Cuba's reborn democracy Gómez was impeached for supposedly obstructing the functions of Congress and replaced with his vice-president Col. Fedérico Laredu Bru, the last veteran of Cuba's wars of independence to occupy the presidency. It was during this period that Cuba received nearly a half-million refugees from fascism and communism in Europe, the largest number per capita of any country in the world.

The Revolution of 1933 saw the rise to power of two men who would dominate Cuban politics for the next quarter century — Ramón Grau San Martín and Fulgencio Batista. The first was a professor at the University of Havana and the latter an army sergeant. On the same side in the wake of the 1933 Revolution both men would become bitter political rivals in its aftermath.

All parties and ideologies would coalesce, however, in 1939-1940 to create the greatest monument of the Cuban Republic, the Constitution of 1940, which became the model of France's Fundamental Law (1958) and other progressive constitutions.

Cuba was then about to embark on the most glorious period in its history, which saw it become the most democratic and prosperous country in Latin American with a standard of living which was comparable to Europe's.

In Part II we will discuss the the rise and fall of the Cuban Republic, which is all the more remarkable because Cuba reached its zenith and nadir at the same time.

The Cuban Republic came into being after a War of Independence that resulted in the death of nearly a quarter of Cuba's population and the destruction of most of the island's infrastructure and economy. In addition to such internal problems, Cuba also had to deal with the intervention and occupation of the island by the U.S. after the conclusion of the Spanish-American War (1898), a minor but calamitous episode within the context of the greater Cuban War of Independence begun by José Martí (1895-1898).

The Cuban Republic succeeded despite the great obstacles placed in its way by U.S. imperialism at its birth. These obtacles Cubans never ceased to fight and eventually defeated long before Castro came on the stage to renew a conflict that had already been resolved largely in Cuba's favor.

Cuba's first democratically-elected president (1902-1906), Tomás Estrada Palma, defeated an American attempt to acquire not one but ten military bases on the island as well as the Isle of Pines (Cuban ownership of which was confirmed in the Hay-Quesada Treaty). He also insisted that the one base that was granted to the Americans be leased rather than ceded, which meant that Cuba still retained sovereignty over Guantánamo thereby setting the stage for its return some day to Cuban jurisdiction. In fact, Guantánamo Naval Base would have been returned decades ago if it had not been for Castro, as the Panama Canal was returned to Panamanian jurisdiction. President Estrada Palma was known as the "Honest President" because he broke with the tradition of graft and corruption introduced to Cuban political life by the Americans.

Estrada Palma was succeeded in the presidency, after an armed uprising quelled by the U.S. at his request and another brief U.S. occupation (1906-1909), by his democratically-elected rival José Gómez, whose administration (1909-1913) was characterized by both its corruption and the full recovery of Cuba's economy from the ravages of the recent war.

Gómez was succeeded in turn, also as a result of democratic elections, by Mario García Menocal, the first and only Cuban president to serve two consecutive terms (1913-1921). The major event of his administration was the First World War, which brought unprecedented prosperity to Cuba as the price of sugar climbed to astronomical levels never to be seen again. Although Menocal joined the Allied side in the War and even instituted a draft, he refused repeatedly U.S. requests to send Cuba's sons overseas to fight in Europe under the American flag. The war ended without a single Cuban casualty. Cuba also joined the League of Nations, which the U.S. did not. A Cuban, in fact, served as its president, which proved that the world as a whole accepted Cuba's sovereignty despite American intrusions on it.

Menocal was succeeded in democratic elections by Alfredo Zayas (1921-1925), a nationalist who also defied U.S. interests in Cuba. Zayas' administration was corrupt; but when the even more corrupt administration of Warren G. Harding sought to impose on him an "honest cabinet" of its own choosing, Zayas at first assented (to get the U.S. war ships threatening intervention to go home) and then immediately fired the U.S. puppets and appointed his own men. This was the first time that the U.S. had been openly defied in Cuba and the U.S. did nothing. This lesson would not be lost on the Cuban people.

Zayas was succeeded, yet again in democratic elections, by Geraldo Machado (1925-1933), the most popular Cuban president as well as the most unpopular. His public works programme transformed Cuba into a modern nation. He built the Capitol as well as the Central Highway, which ran the whole length of the island, among hundreds of other civil works projects. He was so popular that at one time all the Cuban political parties supported him. Machado had made a pledge when he was elected not to seek re-election. He kept this pledge by convincing Congress to prolong his presidential term, which it did gladly. The Cuban people did not receive this violation of Cuban democracy as gladly, however. This "prolongation of powers" led to Cuba's first popular revolution, which succeeded in ousting the democrat turned dictator. Machado believed that this revolution was abetted by the U.S. and before resigning made anti-American declarations for the first time in Cuban political history. The Machado opposition was even more nationalistic and anti-American in its rhetoric.

The Revolution of 1933, with its succession of provisional presidents, juntas and even a counter-revolution, nevertheless succeeded in abrogating in 1934 the Platt Amendment, which had been imposed in 1902 and gave Americans the right to intervene at will in Cuba to protect "our" (read their) interests. With the scrapping of the Platt Amendment Cubans exercised for the first time full national sovereignty. There would be no more American interventions in Cuba. Martí's dream and the dream of all Cuban patriots was finally realized thanks to Cuban resolve and another Roosevelt's "Good Neighbor" policy, which was itself the product of American experiences in Cuba.

If there is a revolution that Cubans should celebrate it is the Revolution of 1933, which was everything that a future revolution was not — nationalistic, progressive and brief. The 1933 Revolution endowed the Cuban people with social rights that no other people on earth enjoyed or would enjoy for decades, including paid maternity leave and a 35-hour work week (for which the employee was entitled to 40 hours compensation). It avoided, moreover, the fashionable extremes of the age, shifting neither to the right and fascism, nor to the left and communism.

Although the Generation of 1933 hated Machado and his cohorts no less than the Generation of 1953 despised Batista and his, the death penalty was not imposed on any of the collaborators of the regime: capital punishment for political crimes was then unknown in Cuba and the firing squad had not been used on the island since colonial times.

The greatest virtue of the 1933 Revolution — the reason for its success, if you will — was its exemplary brevity. In just three years (1933-1936) it had run its course and normality was restored to the island. The final act of the 1933 Revolution was the Amnesty Law of 1936 which freed all Machado officials held in detention (very few) and restored to them their full civil rights. In the elections also held that year many of them were returned to office, one even became Speaker of the House of Representatives.

In the 1936 presidential elections Josê Mariano Gómez, son of Cuba's second president, was elected its sixth constitutional president. In a further test of Cuba's reborn democracy Gómez was impeached for supposedly obstructing the functions of Congress and replaced with his vice-president Col. Fedérico Laredu Bru, the last veteran of Cuba's wars of independence to occupy the presidency. It was during this period that Cuba received nearly a half-million refugees from fascism and communism in Europe, the largest number per capita of any country in the world.

The Revolution of 1933 saw the rise to power of two men who would dominate Cuban politics for the next quarter century — Ramón Grau San Martín and Fulgencio Batista. The first was a professor at the University of Havana and the latter an army sergeant. On the same side in the wake of the 1933 Revolution both men would become bitter political rivals in its aftermath.

All parties and ideologies would coalesce, however, in 1939-1940 to create the greatest monument of the Cuban Republic, the Constitution of 1940, which became the model of France's Fundamental Law (1958) and other progressive constitutions.

Cuba was then about to embark on the most glorious period in its history, which saw it become the most democratic and prosperous country in Latin American with a standard of living which was comparable to Europe's.

In Part II we will discuss the the rise and fall of the Cuban Republic, which is all the more remarkable because Cuba reached its zenith and nadir at the same time.

Thank's Manuel for this wonderful history lesson, enjoyed reading it very much, it's never too late to learn.

ReplyDeleteA bit of trivia, my mom was a child during the Machado regime, she remembers sitting in front of her house and watching cars go by dragging a poor person behind, she claims it was a very bloody time, after his time in office was prolonged of course, my grandma claims that he was loved very much during his first term, if Machado asked someone in the streets Que hora es? the people would reply La que usted quiera mi general, of course I have no way of knowing if these things are true, only what I have been told

Very instructive Manuel.... When people read your whole series they will realize that the history of Cuba was assassinated -along the culture and the traditions by fidel castro, just because he could not compete with his predecesors in office. He would never have been elected dog catcher in el Cotorro!

ReplyDeleteVana:

ReplyDeleteThe student activists who toppled Machado are now very old men, and if you ask them which Cuban president was the greatest, they will answer to a man that it was Gerardo Machado. In fact, for the last 50 years or so, that has been the near unanimous reply of the generation which reviled and demonized him.

The opinion which Cubans held about Machado began to change shortly after his death in 1939 when his will was probated in Miami and it was discovered that he had left a personal fortune totalling a paltry $84,000. For a man who handled hundreds of millions in loans from New York banks to build the Capitol building and the Central Highway, to have left an estate valued at $84,000, shows, if nothing else, that Machado was our other honest president.

Charlie:

ReplyDeleteIf they carry nothing else away from reading this précis, let it be that Cuba was once a civilized nation, and that we should embrace our past with pride and not be swayed by the lies of those who must tear down that past in order to vindicate a present that lags behind the past in every respect.

I certainly hope that we can bring a future to fruiton that would compete with our own past for the betterment of the nation. If we can't do such a thing, at least we have tried, and we will have to live with the monument to what the nation once was.

ReplyDeleteCharlie:

ReplyDeleteOur great national tragedy is that the past is unrecoverable, the present unbearable, and the future unfathomable.

Wow Manuel I guess us Cuban were pretty hot headed then, we toppled just goverments at the drop of a hat,to know in retrospect that Machado was an honest man,and yet they removed him from power, now look at us, same piece of shit dictatorship for almost 50 years, pray tell me Manuel what has happened to us, why have we not toppled this one? do you think it could be because so many of us left the country, and didn't stay to make a difference? oh my I feel so guilty about it, even though I did not leave of my own accord, (Operacion Pedro Pan) the guilt is still there.

ReplyDeleteVana:

ReplyDeleteBefore Castro, Cubans had never known a real dictator. Machado certainly wasn't one and neither was Batista. Although both were military men neither had a penchant for bloodshed. Cubans perhaps thought that at worst Castro would be no worse than Machado or Batista. It was a grave miscalculation, for though Machado and Batista had no history of gratuitous bloodshed, Castro certainly did from his earliest student days.

So fiercely independent and zealous of their rights were Cubans once, even in the face of what was then perceived as tyranny, that when the government tried to raise the bus fare by one cent, university students literally pick up a city bus and carried it up the monumental stairs of the University of Havana, and sent the bus crashing down.

Their grandchildren today, tamed by a real dictator, are nothing less than slaves of the State and receive wages comparable to that miserable centavo.

What has happened? Castro has crushed the revolutionary spirit of the Cuban people which actually required a modicum of freedom, such as Batista and Machado afforded, to be exercised.

Under an absolute tyranny such as Cuba has suffered for the last 48 years, Cubans are as docile as they were formally rebellious.

Now we're talking Manuel! Thank you! This is much needed.

ReplyDeleteOh, and Kudo's on this little gem in your comments:

"Our great national tragedy is that the past is unrecoverable, the present unbearable, and the future unfathomable."

songuacassal:

ReplyDeleteThank-you again for your kind words which are always appreciated. I am, of course, myself in all my writings, including my critiques of Babalú. Over the last two months I have sublimated much my anger and now I mostly aim a humorous pen at your esteemed colleagues. As the bitterness dissipates, I can afford the luxury of humor. And humor, in turn, is a great tonic for the soul (mine, and, from what testimonies have been left here, everybody else's as well).

I have written hundreds of articles about Cuba in my life, and I intend to reproduce the most relevant here, which add both depth and balance to the discussion.

With time Val and Henry may even disappear from this discussion but not anytime soon.